Thursday, March 06, 2008

Left-handers

There are a handful of papers in academic journals that analyse cricket statistics. The methods used in these papers tend to be far more sophisticated than what I use (and usually I don't even understand them), but often the results are interesting and/or useful. Unfortunately, they tend to languish in academic journals, unknown by the average cricket fan. To try to remedy this, every now and then I'll have a look at one of these papers and discuss the methods and results.

The first paper I'll look at is by Robert Brooks et al. It's called Sinister strategies succeed at the cricket World Cup, and was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society Series B (Biology Letters, Supplement) 271: S64. You can get a copy from the website of one of the authors here.

The authors studied the 2003 World Cup, in an attempt to see work out why left-handers are more prevalent in top-level cricket than in the general population. Cricket's not unique in this regard — most sports involving one-on-one contests have a higher proportion of left-handers. Individual sports (such as athletics or golf) do not.

My own feeling was that a large part of left-handed batsmen's success is because the stock ball of right-arm pacemen usually swings into them, and inswingers are easier to play than outswingers. But this paper by Brooks gives strong evidence to suggest that it's more a case of bowlers not being used to bowling to left-handers.

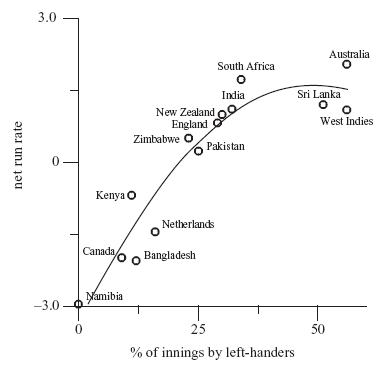

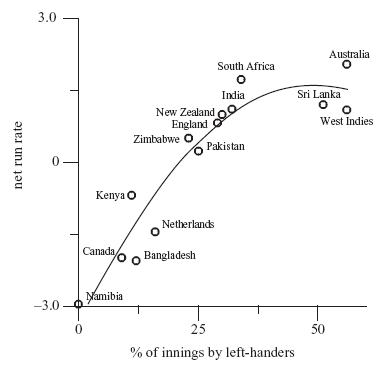

The paper draws out two effects. The first is that weaker countries have a lower proportion of left-handers. The suggested reason is that when the domestic competition is weak, natural talent is the biggest factor in getting selected for the national side — the variation in talent is large enough so that the left-handers' natural advantage is not important. But at a stronger level of competition, where there is less variation in players' ability, the extra advantage that left-handers have becomes more important, leading to disproportionately many of them in national teams. Their figure below shows the trend:

On the vertical axis is the team's net run rate (i.e., how good they are), and on the horizontal axis is the percentage of innings by left-handers. They've fitted a quadratic to the data, which gives a pretty good fit. The interesting feature is that the quadratic peaks at close to 50% left-handers, suggesting that the ideal batting line-up should have an equal number of left- and right-handers.

Now, the obvious explanation for this is that teams with equal numbers of right- and left-hand batsmen enjoy lots of opposite-handed partnerships, and it is an accepted piece of wisdom that bowlers struggle when having to change their line when the batsmen rotate the strike.

But this does not look to be a significant factor. The authors looked at each batsman when they were in partnership with someone of the same hand or with someone of the opposite hand, and found no significant difference. There's some mixed evidence on the usefulness of left-right partnerships. In The Best of the Best, Charles Davis says that left-right opening partnerships (in Tests) average about 15% more runs than would be expected based on the individual averages, whereas same-handed partnerships are about average. My own figures, based on a regression on opening batsmen's averages, puts left-right combinations at 6% better than they should be, and same-handed partnerships 4% worse. But there is plenty of individual variation. It does certainly look like there's a real effect, but you need a large dataset to see it — much larger than just one World Cup — and this is why the authors of the paper didn't find anything significant.

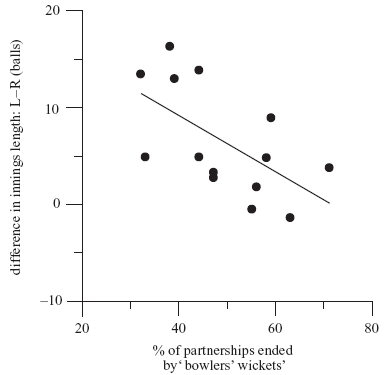

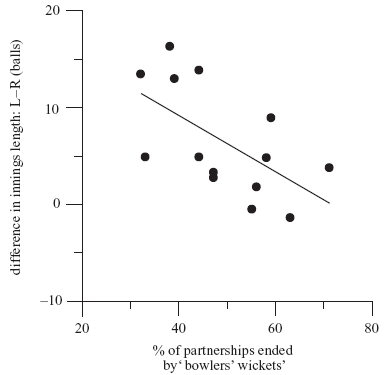

Nevertheless, if there is an advantage to having 50% of the team left-handed, and left-right partnerships are not significant or small, then there has to be something else. The authors show us the following graph.

On the horizontal axis is the percentage of "bowlers' wickets" for each team, and on the vertical axis is the difference between balls faced by left-handers and right-handers by the batting team. Bowlers' wickets are defined as catches from edges, LBW's, and bowleds. They had to do a lot of trawling through Cricinfo's commentary archives to find catches that were at slip!

The trend here is pretty obvious. When there are more bowlers' wickets (suggesting stronger bowling attacks... or really bad fieldsmen), left-handers don't enjoy as much of an advantage over right-handers. The explanation offered by the authors is that weaker bowlers tend to come from weaker competitions, where there are not so many left-handed batsmen. So these bowlers aren't as used to bowling to left-handers so much.

This gives us a reason for the optimum of 50% left-handers. Any more than 50%, and the bowlers would be so used to lefties than right-handers would start to have an advantage.

So it looks like most of the left-handers advantage comes down to bowlers not being used to bowling at them. But the overall story is certainly more complicated. In The Best of the Best, Davis shows that players who bowl right and bat left do better, on average, than players who bowl left and bat left. Is this because the top hand is more important, so that's where you want your dominant hand? Who knows? Players who bowl left and bat right do worse than players who bowl right and bat right. I don't understand.

The first paper I'll look at is by Robert Brooks et al. It's called Sinister strategies succeed at the cricket World Cup, and was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society Series B (Biology Letters, Supplement) 271: S64. You can get a copy from the website of one of the authors here.

The authors studied the 2003 World Cup, in an attempt to see work out why left-handers are more prevalent in top-level cricket than in the general population. Cricket's not unique in this regard — most sports involving one-on-one contests have a higher proportion of left-handers. Individual sports (such as athletics or golf) do not.

My own feeling was that a large part of left-handed batsmen's success is because the stock ball of right-arm pacemen usually swings into them, and inswingers are easier to play than outswingers. But this paper by Brooks gives strong evidence to suggest that it's more a case of bowlers not being used to bowling to left-handers.

The paper draws out two effects. The first is that weaker countries have a lower proportion of left-handers. The suggested reason is that when the domestic competition is weak, natural talent is the biggest factor in getting selected for the national side — the variation in talent is large enough so that the left-handers' natural advantage is not important. But at a stronger level of competition, where there is less variation in players' ability, the extra advantage that left-handers have becomes more important, leading to disproportionately many of them in national teams. Their figure below shows the trend:

On the vertical axis is the team's net run rate (i.e., how good they are), and on the horizontal axis is the percentage of innings by left-handers. They've fitted a quadratic to the data, which gives a pretty good fit. The interesting feature is that the quadratic peaks at close to 50% left-handers, suggesting that the ideal batting line-up should have an equal number of left- and right-handers.

Now, the obvious explanation for this is that teams with equal numbers of right- and left-hand batsmen enjoy lots of opposite-handed partnerships, and it is an accepted piece of wisdom that bowlers struggle when having to change their line when the batsmen rotate the strike.

But this does not look to be a significant factor. The authors looked at each batsman when they were in partnership with someone of the same hand or with someone of the opposite hand, and found no significant difference. There's some mixed evidence on the usefulness of left-right partnerships. In The Best of the Best, Charles Davis says that left-right opening partnerships (in Tests) average about 15% more runs than would be expected based on the individual averages, whereas same-handed partnerships are about average. My own figures, based on a regression on opening batsmen's averages, puts left-right combinations at 6% better than they should be, and same-handed partnerships 4% worse. But there is plenty of individual variation. It does certainly look like there's a real effect, but you need a large dataset to see it — much larger than just one World Cup — and this is why the authors of the paper didn't find anything significant.

Nevertheless, if there is an advantage to having 50% of the team left-handed, and left-right partnerships are not significant or small, then there has to be something else. The authors show us the following graph.

On the horizontal axis is the percentage of "bowlers' wickets" for each team, and on the vertical axis is the difference between balls faced by left-handers and right-handers by the batting team. Bowlers' wickets are defined as catches from edges, LBW's, and bowleds. They had to do a lot of trawling through Cricinfo's commentary archives to find catches that were at slip!

The trend here is pretty obvious. When there are more bowlers' wickets (suggesting stronger bowling attacks... or really bad fieldsmen), left-handers don't enjoy as much of an advantage over right-handers. The explanation offered by the authors is that weaker bowlers tend to come from weaker competitions, where there are not so many left-handed batsmen. So these bowlers aren't as used to bowling to left-handers so much.

This gives us a reason for the optimum of 50% left-handers. Any more than 50%, and the bowlers would be so used to lefties than right-handers would start to have an advantage.

So it looks like most of the left-handers advantage comes down to bowlers not being used to bowling at them. But the overall story is certainly more complicated. In The Best of the Best, Davis shows that players who bowl right and bat left do better, on average, than players who bowl left and bat left. Is this because the top hand is more important, so that's where you want your dominant hand? Who knows? Players who bowl left and bat right do worse than players who bowl right and bat right. I don't understand.

Comments:

<< Home

It is quite intriguing.

I am a right hander in everything i do - always have been. Writing, batting, bowling all right handed. But when it comes to pool / snooker I play left handed. Never understod why.

My younger brother is right handed in everything he does except batting. He bats left handed. Again never understood why.

I am a right hander in everything i do - always have been. Writing, batting, bowling all right handed. But when it comes to pool / snooker I play left handed. Never understod why.

My younger brother is right handed in everything he does except batting. He bats left handed. Again never understood why.

That's very strange that you'd change hands to play pool!

There are lots of people who do everything with one hand except batting. I haven't actually heard many people's reasons for doing so - maybe it's just the luck of how they stood when they first picked up a bat. My favourite story is of Mike Hussey. There's video of him when he was about 10 years old batting right-handed. But his hero was Allan Border, so he decided to switch. It certainly worked for him!

There are lots of people who do everything with one hand except batting. I haven't actually heard many people's reasons for doing so - maybe it's just the luck of how they stood when they first picked up a bat. My favourite story is of Mike Hussey. There's video of him when he was about 10 years old batting right-handed. But his hero was Allan Border, so he decided to switch. It certainly worked for him!

Fascinating. I've always been pretty much both-handed but with a slight bias to my right, so this topic has always interested me.

I like that the leftie's advantage is due to scarcity, so that there's a limit to how many lefties will bring an advantage as the position should automatically correct itself. It's like natural market forces, in a way.

Incidentally I always put on makeup with my right hand, but I have a friend who switches hands, so right hand for her right eye, left hand for her left eye.

I like that the leftie's advantage is due to scarcity, so that there's a limit to how many lefties will bring an advantage as the position should automatically correct itself. It's like natural market forces, in a way.

Incidentally I always put on makeup with my right hand, but I have a friend who switches hands, so right hand for her right eye, left hand for her left eye.

Miriam, I never expected someone to comment about make-up on a cricket stats blog. But it would be interesting (well, maybe not that interesting) to see a survey of make-up wearers and see what the correlation is between natural handedness and the hand used for each eye.

Yes, it is rather incongruous isn't it, but then I revel in incongruity.

I think that most women put makeup on with their main hand, i.e. their writing hand, because they'd have to be pretty steady-handed with both otherwise. The obvious exception is nail polish where you don't have a choice.

Coming back to the cricket and in particular the last paragraph of your post, they do say that different sides of the brain do different things, and that this feeds through into what hand you use. Maybe bowling requires some skills that are governed by one side of the brain, and batting by the other side of the brain, so that there might be an intrinsic advantage at play too, which is why the position is more complicated than lefties being scarce and therefore harder to play against.

This whole left-brain right-brain thing: do you happen to have similar stats for women's cricket? That might be interesting.

I think that most women put makeup on with their main hand, i.e. their writing hand, because they'd have to be pretty steady-handed with both otherwise. The obvious exception is nail polish where you don't have a choice.

Coming back to the cricket and in particular the last paragraph of your post, they do say that different sides of the brain do different things, and that this feeds through into what hand you use. Maybe bowling requires some skills that are governed by one side of the brain, and batting by the other side of the brain, so that there might be an intrinsic advantage at play too, which is why the position is more complicated than lefties being scarce and therefore harder to play against.

This whole left-brain right-brain thing: do you happen to have similar stats for women's cricket? That might be interesting.

That's a good question. I don't keep women's stats, so I had a fiddle with Statsguru.

I looked at ODI's between only Australia, England, India, Ireland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, and West Indies. Also, I only looked at batters from positions 1 to 7.

Overall, left-handers average 2.1 more runs. Since 2000, that has increased to 3.2.

Australia has more left-hand batters than any other team since 2000, with 19%. Overall, England is highest at 15%. This suggests, if we follow the reasoning of the Brooks et al. paper, that the pool of top-class players is not as competitive in women's cricket as it is in men's, which makes sense.

There is a pretty good fit when you plot win percentage against percentage of left-handers. Overall, about half of the variance in the win percentage can be "explained" by the percentage of left-handers. This rises to 75% since 2000. That rise might just be luck.

So the same principles appear to apply in women's cricket, but the talent pool isn't big enough for there to be too many left-handers yet.

Post a Comment

I looked at ODI's between only Australia, England, India, Ireland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, and West Indies. Also, I only looked at batters from positions 1 to 7.

Overall, left-handers average 2.1 more runs. Since 2000, that has increased to 3.2.

Australia has more left-hand batters than any other team since 2000, with 19%. Overall, England is highest at 15%. This suggests, if we follow the reasoning of the Brooks et al. paper, that the pool of top-class players is not as competitive in women's cricket as it is in men's, which makes sense.

There is a pretty good fit when you plot win percentage against percentage of left-handers. Overall, about half of the variance in the win percentage can be "explained" by the percentage of left-handers. This rises to 75% since 2000. That rise might just be luck.

So the same principles appear to apply in women's cricket, but the talent pool isn't big enough for there to be too many left-handers yet.

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]